Dissecting Desires: A Rhetorical Analysis on Objectification in Advertising

by Annika Hodges, Eastern Oregon University

Figure 1. Marc Jacobs fashion advertisement.

A woman—or rather, a pair of women’s legs cut off above the knees—sprawl out messily from a crumpled white bag sitting on the ground. The legs, tan, hairless, and spread wide apart, sport a pair of illogically built black and pink high heels, with the heel part on the front of the shoe, rather than the back (see Figure 1). This is the description of an advertisement for Marc Jacobs, a fashion company. This campaign, launched in 2008, marked Victoria Beckham’s debut in the fashion industry and was photographed by Juergen Teller, a celebrated photographer known for his provocative style. The ad received light critique in The New York Times for its unsettling portrayal of women, yet, in the same breath, the article lauded Teller’s creativity, highlighting how such imagery is often dismissed as artful innovation rather than critically examined for its deeper implications. Marc Jacobs is not the only brand known for utilizing women’s body parts, rather than the full women themselves, as a part of their advertising campaigns. One advertisement from Ipanema, a sandals company, features a pair of shiny, hairless women’s legs protruding from a hat (see Figure 2). With one leg straight and the other brushing against it in the classic 45-degree angle pose, the hat rests above the lower portion of the model’s butt cheeks, just barely hiding her pelvic area. Released in 2016, this ad demonstrates how such dehumanizing visual strategies persist across decades and global markets, normalizing the aesthetic fragmentation of women’s bodies. The actual sandals being advertised are the least conspicuous elements, capturing an audience’s attention only after thorough observation.

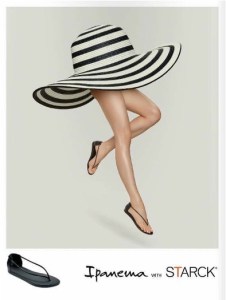

Figure 2. Ipanema sandal advertisement.

These images are more than just simple advertisements; rather, they act as signs, or something that makes you think of something else. By reducing women to their individual body parts, these advertisements become vehicles for conveying complex messages about the role of women in society, both reflecting and contributing to the creation of a culture that views women as objects made of interchangeable parts—objects made to be dissected and consumed. Their prominence—one associated with a high-profile debut for a major global brand, the other released nearly a decade later by an international company—underscores the endurance and reach of such objectifying imagery. In analyzing these images, it becomes apparent that they employ visual rhetorical strategies to construct meaning and affect the audience. Firstly, the deliberate disjointed representations of women, achieved through the structural composition of the images, places a focal point on sexualized women’s body parts, thereby inviting the audience to perceive women as a collection of interchangeable fragments. Secondly, the manipulation of point of view within the images situates the audience in a dominant position over the women depicted, reinforcing power imbalances. Both techniques contribute to the overarching theme of objectification, which can have an impact on women’s mental health and sense of self. My analysis seeks to unveil how these strategies work to perpetuate harmful gender norms and shape societal attitudes toward women as mere objects for visual consumption.

I will start by exploring the objectification thesis and its historical underpinnings, followed by an examination of studies that shed light on the profound effects media can have on both women’s and men’s perceptions of women. In the subsequent sections, the focus will shift toward a detailed analysis of the visual rhetorical strategies employed within the images. Building on these insights, I will then circle back to the theory of objectification, establishing a link between the rhetorical strategies used and their broader societal impact. The final part will encapsulate the essay’s argument, emphasizing the implications of these media representations on women’s mental health and self-perception, ultimately solidifying the argument that these images contribute significantly to a culture that views women primarily as objects for visual consumption.

Objectification Theory

Objectification theory is a conceptual framework that looks at the impact of treating individuals as objects, particularly examining its effects on women and girls. Objectification occurs when a “woman’s body, body parts, or sexual functions are separated from her person, reduced to the status of mere instruments, or regarded as if they were capable of representing her” (Fredrickson & Roberts 175). In other words, when objectified, women are perceived not as complete individuals but instead as bodies that exist for the pleasure and consumption of others. Objectification is explained by perception theory, which

differentiates between two forms of perceptual processing: local processing, where objects are treated as a sum of parts, and global processing, where objects are treated holistically. Object recognition uses local processing, while person recognition largely relies on global processing … The global processing of human bodies is, however, only employed for men, whereas local processing is employed for women. Unlike men, women are perceived more like objects… (Berg 1004).

Objectification theory also suggests that “an individual’s sense of self is a social construction, reflecting the ways that other people view and treat that individual,” which means that the cultural environment of objectification conditions girls and women, prompting them to think of themselves as objects to be dissected and consumed (Fredrickson & Roberts 179). This is called self-objectification, which “can lead to a form of self-consciousness characterized by habitual monitoring of the body’s outward appearance,” often resulting in anxiety, shame, depression, and even eating disorders (Fredrickson & Roberts 180).

Objectification of Women in Advertisements

One of the ways in which the objectification of women is perpetuated in society is through the carefully constructed images used in advertising campaigns. Advertising saturates our daily lives, often slipping into our awareness without conscious acknowledgement. This constant exposure means that the social messages conveyed through advertisements tend to go unchallenged, seeping into our collective consciousness with a subtle, yet enduring, influence. There is evidence suggesting that being exposed to sexually objectifying advertisements leads to the development of anti-woman attitudes. In their study, “Images of Women in Advertisements: Effects on Attitudes Related to Sexual Aggression,” Kyra Lanis and Katherine Covell found that men exposed to advertisements in which women were objectified, compared to men shown more humanizing images of women, were “significantly more accepting of rape-supportive attitudes,” while women exposed to the more humanizing images of women “were less accepting of such attitudes” (639). Additionally, women shown the objectifying advertisements showed less support for feminism than the women who were shown the humanizing advertisements. This is no accident. Between 1958 and 1983, as women started to gain rights and a life outside the home, the prevalence of objectifying advertisements of women increased by sixty percent; even today, women’s presence in advertisements often “has no substantial relation to the product; increasingly, the woman’s role is to be sexy and alluring” (Mackay and Covell 574-574). Advertisements that reduce women to their bodies, or individual body parts, are one way for the objectification of women to continue in society.

Analyzing the Marc Jacobs Advertisement

Images are “focal points for the attribution of meaning” and can be constructed in a specific way “so as to encourage specific attributions of meaning and to discourage others” (Brummett 185). As such, images must be interpreted through the context in which they were created in order for meaning to be discovered. Circling back to the Marc Jacobs advertisement, the audience can see that a focal point is placed on a pair of women’s legs—isolated from the woman herself—jutting out of a Marc Jacobs branded bag. This is a literal representation of objectification, in which a “woman’s body, body parts, or sexual functions are separated from her person” (Fredrickson & Roberts 175). The legs are long, tanned, and spread wide open, which intensifies the sexualized nature of the image. The bag covers what would be assumed to be the woman’s pelvic area, creating an even more deliberate focus on the often overly-sexualized lower body. The choice of a Marc Jacobs branded bag adds another layer of meaning—beyond the obvious of it being an advertisement for Marc Jacobs—by suggesting a commodification of the woman’s body as if it were a product associated with a luxury brand. This association reinforces the idea that the woman is reduced to a symbol or accessory rather than an individual with agency and autonomy. An interesting addition to this advertisement is the fact that it is not representing a specific product but rather the brand itself, further emphasizing the objectification of women as a marketing strategy.

The illogical construction of the high heels, with the heel part on the front of the shoes, adds a significant dimension to the interpretation of the image. Historically, high heels were initially designed for men and served to aid horseback riding or symbolize elevated social status. However, as women began to wear high heels, the heels became taller and thinner, symbolizing sexuality and ornamentality. The modern high heel not only affects a woman’s ability to comfortably walk/run through the world but is also “detrimental to their health” (Barnish 1). The intentional distortion of the high heels in the Marc Jacobs advertisement, with the heel on the front part of the shoe, renders the heels completely unusable, making it clear that the woman in the image cannot get up and walk away in them. By constructing the heels in such a way, the photograph reinforces the meaning created by its implied strategies—that the woman is intended purely for decorative purposes.

Another rhetorical strategy used in images is the point of view in which they place the audience in relation to the image. One way this works is through the “difference between intimacy and distance” (Brummett 190). In viewing the Marc Jacobs advertisement, the audience assumes a position of dominance, situated above the woman, or more specifically, a pair of isolated women’s legs, adopting a perspective that looks down upon the subject of the advertisement. This perpetuates a sense of control and authority, dominance and submission. The audience’s sense of dominance is heightened by the deliberate focus on the pelvic area, which further emphasizes the model’s vulnerability and submission. Furthermore, the illogical construction of the high heels, featuring the heel at the front and rendering them non-functional, symbolizes the woman’s helplessness and reinforces the audience’s position of dominance over her, further reinforcing the objectification depicted in the advertisement. She is there for decorative purposes, not wanted in her entirety, and cannot escape.

Analyzing the Ipanema Advertisement

Similar to the Marc Jacobs advertisement, the Ipanema advertisement reduces women to isolated body parts, specifically emphasizing the sexualized lower body. The focal point of the image is not the sandals being advertised, but rather, the sexualized pair of women’s legs, divorced from the body from which they came. This is a representation of objectification, in which women are treated “as bodies that exist for the use and pleasure of others” (175). The legs are long, tanned, and shiny, which adds to the sexualized nature of the image. One leg is outstretched while the other is brushing up against the straightened leg at a 45-degree angle, creating a classic pose that intensifies the sexualization of the legs. The hat, placed strategically above the lower portion of the woman’s buttocks, serves both as a cover for the pelvic area and, simultaneously, to draw attention to it, perhaps inducing the audience to question what lies underneath. This heightens the sexualized nature of the image. This deliberate focus placed on the fragmentation of the female body aligns with the broader theme of objectification, emphasizing the idea that women are to be viewed as interchangeable pieces rather than complete individuals. The audience’s attention is drawn to the sexualized body parts, reinforcing the perception of women as objects for consumption. While the sandals are the advertised product, they become secondary to the objectified portrayal of the legs. They are not just selling sandals, they are selling sexualization through objectification.

Like the Marc Jacobs advertisement, the Ipanema advertisement uses point of view to position the audience in a dominant position. The viewer looks down upon the isolated pair of women’s legs, adopting a perspective of control and authority. The woman—if there is a woman and not just a pair of legs—is unable to run away, as her upper body is consumed by the hat. Without the entirety of her body, the woman is at a disadvantage to the audience. This reinforces the power imbalance, perpetuating a culture that objectifies women and places them in submissive roles. The intentional framing of the image guides the audience to focus on the sexualized legs from a dominant point of view, contributing to the overall theme of objectification within the advertisement.

Material Implications

Today, women claim more power and agency in the world than ever before: they hold a wider variety of jobs in a wider variety of industries; they own their own businesses; and they’re holding more and more positions of power in the government. However, as there has been an increase in women’s rights, there has also been an increase in the objectification of women through various forms of media, such as television and advertisements. Between 1958 and 1983 alone, there was a sixty percent increase in the prevalence of objectifying advertisements of women (Mackay and Covell 574-574). Women in advertisements often have no relevance to the product and are being utilized solely to sell desire/sexualization through objectification. This is relevant to the issue of women’s rights in the present day, as “there is evidence that exposure to sexually objectifying advertisements produce anti-woman attitudes” (Stankiewicz and Rosselli 581). This has real life implications in that “this appears to be associated with heightened aggressive attitudes towards women” and reinforces “male attitudes supportive of sexual aggression and opposed to women’s efforts to equality” (Mackay and Covell 574-576). Not only do these advertisements affect men’s perception of women, but they also affect women’s perceptions of women. In their article “The Impact of Women in Advertisements on Attitudes Toward Women,” Mackay and Covell found that “females shown the sex image advertisements showed less support for feminism than did those shown the progressive image advertisements” (580).

These images also contribute to self-objectification, in which women and girls “treat themselves as objects to be looked at and evaluated,” often resulting in a “habitual monitoring of the body’s outward appearance” (Fredrickson and Roberts 177-180). This often contributes to shame, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and a reduced participation in life.

For these reasons, it is important for both women and men to be made aware of the ways in which the construction of these advertisements can affect their views on women. This “increased awareness of sexual imagery and its consequences is important for improving the physical and emotional welfare of women and girls” (Mackay and Covell 580). By understanding the implications of these advertisements, individuals can actively resist and challenge societal norms that contribute to the harmful perpetuation of objectification.

Conclusion

The analysis of advertisements from Marc Jacobs and Ipanema reveals a disturbing reality ingrained in our society—a reality where women are reduced to isolated body parts for the visual pleasure and consumption of the audience. The deliberate reduction of women to sexualized fragments and the manipulation of point of view within the images create a narrative of objectification, reinforcing power imbalances and influencing societal attitudes toward women.

Objectification theory provides a conceptual framework to understand the impact of treating women as objects. The prevalence of objectifying advertisements in our daily lives has been associated with anti-woman attitudes and the perpetuation of gender inequality. Women, portrayed as interchangeable fragments, face the risk of internalizing these harmful stereotypes, leading to self-objectification and a range of negative mental health outcomes. The correlation between exposure to objectifying images and anti-woman attitudes reinforces the need for societal awareness and action.

To counter the detrimental influence of these advertisements, promoting media literacy and critical analysis is imperative. Individuals must actively resist and challenge normalized objectification, fostering a cultural shift toward a more inclusive, respectful, and holistic portrayal of women. By confronting and challenging deeply ingrained norms, society can pave the way for a future where women’s achievements are celebrated without compromising their dignity and agency.

Works Cited

Barnish, Max, et al. “The 2016 High Heels: Health Effects and Psychosexual Benefits (High Habits) Study: Systematic Review of Reviews and Additional Primary Studies.” BMC Public Health, vol. 18, no. 1, 1 Aug. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4573-4.

Berg, Hanna. “Headless: The Role of Gender and Self-Referencing in Consumer Response to Cropped Pictures of Decorative Models.” Psychology & Marketing, vol. 32, no. 10, 2015, pp. 1002–16, https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20838.

Brummett, Barry. Rhetoric in Popular Culture. SAGE, 2018.

Fredrickson, Barbara L., and Tomi-Ann Roberts. “Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks.” Psychology of Women Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 2, June 1997, pp. 173–206, doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Lanis, K., and K. Covell. “Images of Women in Advertisements: Effects on Attitudes Related to Sexual Aggression.” Sex Roles, vol. 32, no. 9–10, 1995, pp. 639–49, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01544216.

Mackay, N. J., and K. Covell. “The Impact of Women in Advertisements on Attitudes Toward Women.” Sex Roles, vol. 36, no. 9–10, 1997, pp. 573–83, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025613923786.

Stankiewicz, Julie M., and Francine Rosselli. “Women as Sex Objects and Victims in Print Advertisements.” Sex Roles, vol. 58, no. 7–8, 2008, pp. 579–89, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9359-1.

—

Annika Hodges recently graduated from Eastern Oregon University with a BA in English/Writing and is working as the editor-in-chief of the Applegater, a small newspaper in Southern Oregon. When she’s not busy putting pen to paper, she enjoys reading, hiking, backpacking, geocaching, and lifting weights.

You must be logged in to post a comment.