Quinni Gallagher-Jones: Exploration of the Heartbreak High Character’s Autistic Representation

by Ileana Oeschger

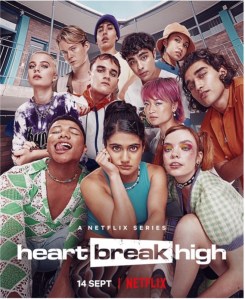

Fig. 1. Hayden, Chloé. “Heartbreak High Netflix Release.” Instagram, 14 Sept. 2022.

Young autistic women are a forgotten group. According to recent studies, the ratio of males to females with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD ) is 4:1, and most researchers argue there is a large gender bias behind this phenomenon (McCrossin). As they grow up, young girls learn quite quickly that the world does not tolerate strange or outspoken women, and that their socialization holds much higher expectations than that of their male peers. So, they figure out how to mask—the conscious and unconscious suppression of a person’s autistic experience and identity, downgrading and downplaying their neurodivergence to appease a very neurotypical-pleasing society, and eventually, they become undetectable in public (Frankly TV 2022). This difference in socio-communication abilities, and lack of research surrounding the difference, has created a diagnostic delay for autistic women; around eighty percent of autistic young women remain undiagnosed until the age of eighteen (McCrossin). This issue is reflected in the media as well, with most mainstream shows choosing white, heterosexual young men for autistic characters, often framing them as ‘the antisocial genius’. However, this year, a Netflix series called Heartbreak High challenged this common stereotype. The Australian series focuses on a group of teenagers navigating relationships and new sexual experiences, while cleverly and carefully touching on important themes such as mental illness, queer identity, racism, police brutality, and sexual assault. Most notably, the show includes main-character Quinni Gallagher-Jones, who is now one of the most accurate representations of female autism in mainstream media. Furthermore, Quinni is played by Chloé Hayden, an autistic social media star and disability rights activist. Quinni’s identity as a queer and autistic woman in the series, along with the media context behind the actress herself, has created an incredible opportunity for mainstream discourse and representation of feminist, queer, and disabled communities. This paper will focus on analyzing the benefits and drawbacks of Quinni’s character in regard to intersectionality and positive representation.

Foundations of Intersectionality

Beforehand, it is imperative to first explain the significance of intersectionality in this analysis. Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term ‘intersectionality’, argued that a single-axis framework of discrimination could not address individuals who held multiple marginalized identities. The foundations of intersectional media studies were built by American women of color scholars and European feminist scholars, and then grew further thanks to the next generation. Scholars Isabel Molina-Guzmán and Lisa Marie Cacho explain that contemporary queer and feminist scholars are bringing in new works centered on media representations and intersectionality of not only gender and race, but ethnicity, citizenship, and nationality. This shift in media studies, the authors write, has grown from the understanding that “intersectionality really is about embodiment—about negotiating a sense of self through pre-scripted social identities disseminated by media and popular culture” (Molina-Guzmán and Cacho 74). In other words, media representation and identity should be seen as interconnected, both undermining and reinforcing one another. A character such as Quinni needs to be observed through this point of view; she cannot solely be understood as a media representation, her multiple identities create a sense of self that serves as a reflection for real-life individuals. So, in this analysis, Quinni will be looked at with an intersectional perspective in mind.

As the author, I must acknowledge that my identity as a white, queer, autistic, and physically disabled woman from the United States may impact how this paper is written. My positionality as an American white woman greatly reduces my understandings of the racial contexts that exist within Heartbreak High, since the show is set in Australia. I can only effectively analyze Quinni’s character through the lens of American notions of whiteness. Additionally, because I resonate so deeply with the portrayal of the queer and disabled experience in this show, my analysis may also be biased towards the positives of her representation. However, my personal connection to Quinni has also aided in the depth and richness of my analysis, as I approached the work with great care. Thus, despite these limitations, I aim to analyze the representation and intersectionality of Quinni’s character to the best of my ability.

Autistic Representation

As previously stated, Quinni Gallagher-Jones is an autistic female main character on Netflix, a mainstream television network. Her presence in Heartbreak High is incredibly significant because it challenges most autistic representation in media, which is narrow, one-dimensional , and only focuses on men. In the academic search, “Characters with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fiction: Where Are the Women and Girls?”, it was discovered that many TV portrayals of autism had audiences that speculated about whether the characters were autistic, but writers never clarified . It is possible, the researchers in the study explained, that being vague about the character’s neurotype means television writers have less of a responsibility to create an accurate portrayal of autism and can easily poke fun at autistic people without it being outwardly ableist. Additionally, many of the female characters found in this search either had a stereotypical presentation of autism, with overly exaggerated behaviors to create an interesting and dramatic scene; or a sanitized presentation, also known as ‘cute autism’, where the focus is on infantilizing abnormality. This type of representation cannot continue, as it is limited and harmful. Considering that “forms of fiction, such as film, have the ability to educate viewers, it is important that character representations are suitably realistic, authentic and nuanced” (Tharian 51). Quinni is a character that offers such nuance.

Multi-Dimensional Representation

Quinni is not portrayed as a one-dimensional autistic character. Her autistic traits are intentionally incorporated in the show as they are consistent and naturally embedded into her personality rather than being used to stereotype or simplify her. From the first episode, she is shown subtly stimming with her hands in class and covering her ears during loud noises. She also experiences moments of social confusion with her peers and asks blunt questions to clarify. Quinni also attends a party with her friends and talks about sex, challenging the inaccurate media stereotypes that argue autistic people enjoy neither parties nor sex. By the second episode, it is confirmed that Quinni is autistic when she tells her romantic love interest, Sasha. Due to her limited understanding of autism and internalization of stereotypes, Sasha tries to find a way to say the “you don’t look autistic” phrase without offending Quinni, a conversation that autistic people know all too well. Quinni then gives an incredible response, explaining how she hides most of her traits by masking, and turns confidently to leave when she begins to feel disrespected. However, Sasha admits she has learning to do, and they make amends. With this one scene, the show already surpasses most mainstream representations of neurodivergent individuals.

The Joys and the Struggles

In Episode Six, Angeline, viewers get an even closer look into Quinni’s character as they see her getting ready in the morning, following a routine she’s written on a list beside her bed. The bedroom is filled with an extensive collection of comfort items (stuffed animals, trinkets, books) and decorations of her special interest , Angeline, her favorite book series. She gets dressed in her eccentric style and applies her colorful makeup, a nod to the way autistic people often outwardly express themselves in a more unique and un-filtered way compared to their allistic peers . Furthermore, as she puts on her sweatshirt, she cuts off the tags to prevent discomfort due to texture sensitivity . Finally, she heads outside and watches a flock of birds fly by in awe, as even the simplest things can appear quite incredible to the autistic brain. These details, while likely unnoticed by most allistic people, resonate deeply to the autistic women watching; it is how they see the world. However, the show does not simply focus on autistic joy, or the ‘cute’ and consumable side of autism. As the episode goes on, Quinni finds herself navigating stressful changes to her plan she had made to attend a book signing related to her special interest. As the day goes on, she starts to feel overstimulated by the noises of the bus. Instead of being supportive, Quinni’s girlfriend treats her with judgment and ableism, leading them into a painful argument. Afterward, Quinni comes home and experiences a meltdown . Each person experiences meltdowns differently, however many autistic women became very emotional from this scene because it is the first time their type of meltdown has been represented on television. Quinni also appears at school the following few days with noise-canceling headphones and is shown going through a nonverbal episode . These are two common experiences, especially after a meltdown, for autistic people that are rarely shown in mainstream media. Heartbreak High’s choice to include these scenes, with both the good and bad parts of Quinni’s life, is incredibly significant. While autism is a magical and brilliant experience, it is also a painful struggle and clashes with the neurotypical world. It is important that both sides of ASD, and everything in between, are represented.

Autistic Lesbian Representation

Along with being autistic, Quinni also identifies as a lesbian. Her queerness is simply part of her, as she is already out, and is encouraged and supported by her peers. In her article analyzing Heartbreak High, author Charli Clement explains how this aspect adds another major level of representation to Quinni’s character. She writes, “While autistic people are more likely to be LGBTQ+ than non-autistic people, this is an intersection rarely explored in television or film” (Clement 2022) . As stated earlier, most autistic characters in television shows are heterosexual men. Quinni, therefore, is a rare and important representation for both queer and autistic audiences. In the second episode, Quinni begins a new relationship with a neurotypical character, Sasha. The couple is shown navigating queerness without being targeted by homophobia or violence, which is often the route television decides to take. Instead, they are completely open at school and are met with celebration by their friends and family. The relationship is everything it should be: energizing, slightly awkward, and incredibly sweet. Unlike other shows, their queerness isn’t used as a dramatic or stressful plot, it is simply an exciting and new beginning for the two teenagers. Clement also points out the significance of audiences seeing an autistic person in a romantic relationship like this one, because it is something many neurotypical and neurodivergent people believe cannot exist. “Not only this,” she writes, “but Quinni is engaged with her own sexual attraction and arousal, discussing having sex – often even more avoided by the media than romantic relationships when it comes to autistic individuals” (Clement 2022). As things progress, Quinni and Sasha talk about having sex with one another, and they eventually do, off-screen. The show is also careful to include PDA that is natural and realistic for two teenagers without it being over-sexualized, something that often happens with lesbian scenes in media. Unfortunately, the relationship begins to crumble as Sasha continues to misunderstand and ignore Quinni’s needs and starts to take responsibility for her; something Clement states is often a common conflict for allistic-autistic couples. Allistic people often over-infantilize their autistic partners, assuming a role of caretaker when they were not asked to do so. Finally, in an argument scene, Quinni is faced with ableism from her partner. Sasha angrily expresses frustration for not being able to be a ‘normal teenager’ because she’s always doing things ‘for’ Quinni, even though there was no expectation for her to do so. She tells Quinni not to ‘pull the autism card’, and that her autism is a lot for herself. In an emotional response, Quinni says, “It’s a lot for me too Sasha. It’s my whole life”. Overall, the relationship between the two girls brings to mainstream media “the ups and downs not only of a high-school relationship amongst teenage dramas, school difficulties and friendship troubles, but one that is navigating identity, queerness and disability” (Clement 2022). Sasha and Quinni provide an on-screen experience that autistic and queer individuals can fully relate to.

Lesbian Representation: Benefits and Drawbacks

While Quinni provides representation for the queer and autistic community, her character falls into a specific category of media depictions: the consumable lesbian. In her article “Making Her (in)Visible Cultural Representations of Lesbianism and the Lesbian Body in the 1990s.”, Ann M. Ciasullo analyzes the phenomenon. She explains that while lesbian representation promises visibility, visibility also means that certain images of lesbians must be chosen as ‘watchable’. This created the consumable lesbian: a white, thin, conventionally attractive, upper middle class, femme body. These women present ‘lesbian chic’; they are sanitized through their feminizing, assuring heterosexual audiences that lesbians are ‘just like us’. While Quinni’s neurodivergence sets her appearance and fashion expression apart from her neurotypical peers, she is still very much a ‘watchable’ lesbian character. Her privilege as a white and femme woman allows for her story and struggles to be taken more seriously by mainstream audiences; it is quite likely straight viewers would skip through her scenes if she was not considered conventionally attractive. Thus, her white/femme/middle-class identities and queer/disabled identities intersect with one another, creating a mix of privilege and oppression that cannot be dissected cleanly.

Important to note as well is Sasha’s character. While Quinni is still a mainstream representation of lesbianism in media, her relationship with Sasha is not. Sasha is an Asian-Australian woman with bright pink hair and an alternative style. Her presence in the show provides audiences with a POC lesbian character, a representation often lost in mainstream media. Sasha and Quinni simply exist in the show as an interracial lesbian couple, navigating joy and hardships, which in many ways is an act of rebellion in and of itself. Thus, while Quinni’s character has its drawbacks regarding her consumable archetype, her relationship with Sasha provides a fuller representation of the lesbian community.

Media Context behind Quinni

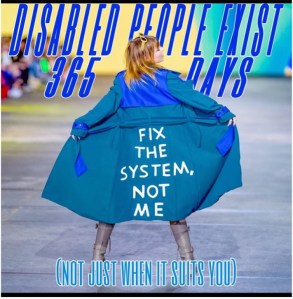

Fig. 3. Hayden, Chloé. “International Day for People with Disability.” Instagram, 2 Dec. 2022.

The representation present for Quinni’s character goes beyond just the screen. The actress who plays her part, Chloé Hayden, is an autistic woman in real life. The 25-year-old actress is a famous disability advocate, motivational speaker, and successful content creator on social media; with 184 thousand followers on Instagram and over 600 thousand followers on TikTok. Her videos inspire her neurodivergent followers and help educate people about disability. Hayden also recently came out with a book, Different Not Less: A Neurodivergent’s guide to embracing your true self and finding your happily ever after. Notably, Hayden has also spoken publicly against Singer-Songwriter SIA for her 2020 movie “Music”, which included harmful stereotypes of autism and casted a non-autistic actress for the main role. With her advocacy and influence, Chloé Hayden has become a huge role model for young autistic women around the world.

Creating Quinni

Fig. 4. Hayden, Chloé. “Woman. Of. The. Year.” Instagram, 10 Nov. 2022.

In a video interview with Fran Kelly, Hayden reflected on playing the character Quinni for Heartbreak High. She explained that the writers of the show consulted with her while crafting the character, saying, “I was so incredibly lucky that I got to have such a hand in creating who Quinni was, and it meant that so much of my story is Quinni’s story, and vice versa” (Frankly TV 0:22-34). The only main difference between the two people, Hayden said, is their access to resources. Unlike the actress at that age, Quinni has a better understanding of her autism, more confidence, and an incredible support network of family and friends. Hayden’s agency over Quinni’s character and personal connection to the autistic experience allowed for the creation of an incredibly realistic portrayal of autism, which in turn provided an accurate and meaningful representation to a large group of young people. “This is why I do what I do”, Hayden expressed, “I do this because I didn’t have representation growing up and knowing that young people can see Quinni and go “I’m okay, I’m supposed to be here, I’m supposed to exist” (Frankly TV 1:56-2:12). In recognition of her outstanding achievements and role in Heartbreak High, Hayden was named “Woman of the Year” in November by Marie Claire and awarded “Audience Choice Best Actress” in December at the AACTA Awards.

Social Media Significance

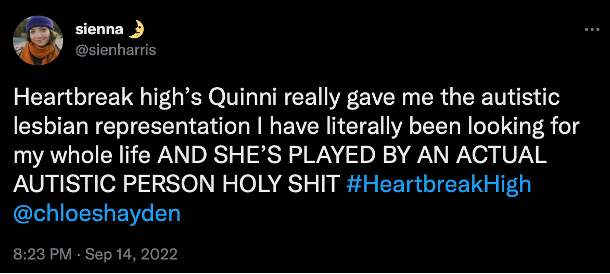

Social media plays an important part in the representation and creation of Quinni’s character. Since meaning in media is a collaborative project, the relationship between creator-show-audience for Heartbreak High is significant to explore. As discussed in the previous section, Quinni’s character is credited to the collaboration between the show’s writers and actress Chloé Hayden. Her social media platform likely provided leverage for her as she worked alongside these writers, as her large following supports her credibility as a disability advocate and relatable autistic creator. Following the release of the show, many people began posting, tweeting, and sharing their praises for Quinni and her representation of autism. Many character edits and reaction videos were created as well (which are included as media supplements in this paper). It was an incredible amount of feedback, with most of the discourse surrounding Quinni’s character occurring on LGBTQIA+ and disabled community platforms. These large platforms exist online because in real life spaces where queer and disabled people can feel safe and empowered are few and far between. In a qualitative study focusing on LGBTQIA+ university students with disabilities, it was found that many of the students “negotiated boundaries between online and offline, often prioritizing the freedom and connections one could experience online, particularly when the notion of a physical space or community that embraced queerness and disability seemed hypothetical” (Miller 520). With the world at their fingertips, these young people can gain more information about their identities, find validation in their experiences, and get involved with activism. At the same time, however, multiple students in the study reported they struggled with marginalization online. While communities for LGBTQIA+ people and disabled people attempt to foster a safe online environment, harm (racism, homophobia, ableism, etc.) can still very much exist in media spaces. Despite these conflicting issues, queer and disabled young people continue to participate, focusing instead on the benefits of their online platforms. It is important to note, that without these communities generating discourses and responses on social media, the meaning behind Quinni’s character wouldn’t be nearly as significant. Their connections to Quinni’s experiences breathed more life into her as a representation of the queer/autistic community, and in doing so, they played a part in creating her.

Moving Forward

From this analysis, it is clear to see that Quinni’s existence in Heartbreak High beautifully challenges the boundaries of representation. Her nuanced experiences in the show intentionally shy away from the ‘cute’ and consumable side of women with autism, creating a multi-dimensional character and providing a realistic depiction of ASD that audiences can learn from. Her privilege as mainstream media’s ‘consumable lesbian’ lessens the significance of this representation, but her relationship with Sasha brings to light an interracial couple navigating queerness and disability. Quinni is certainly not a perfect character in the lens of intersectionality, but she has opened a door in mainstream media that was previously locked shut. Autistic, queer, and disabled people, respectively, can see parts of themselves represented in Quinni, and women who identify as both lesbian and autistic can finally feel as if they’re looking in a mirror when seeing her on screen. As the wonderful actress, Chloé Hayden, said in her acceptance speech for ‘Woman of the Year’, “Understand that different isn’t less, that different is powerful and beautiful and so, so incredibly important. Change is made by being different and it is time that those who are different see how incredible they are” (Marie Claire). Thanks to the collaboration and support of Heartbreak High’s writers, Chloé Hayden, and LGBTQIA+/disabled social media communities, Quinni’s character is reminding those who are different how incredible they are. She is uncovering a population of people that have always existed, but have never been seen, and this uncovering must continue. Heartbreak High gave the media industry a wonderful example of queer and autistic representation, and one can only hope it will be followed by new and more inclusive shows in the future. Because, if anything, the world needs and deserves more representation like Quinni Gallagher-Jones.

Works Cited

Bassi, Isha. “‘I’ve Never Seen My Experience Represented like This before’: Fans Are Sharing the Meaningful Impact ‘Heartbreak High’ Has Had on Them.” BuzzFeed, BuzzFeed, 26 Sept. 2022, https://www.buzzfeed.com/ishabassi/heartbreak-high-netflix-fan-reactions-representation.

Ciasullo, Ann M. “Making Her (in)Visible: Cultural Representations of Lesbianism and the Lesbian Body in the 1990s.” Feminist Studies, vol. 27, no. 3, 2001, p. 577. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178806.

Clement, Charli. “Why Heartbreak High’s Autistic Queer Representation Is so Groundbreaking.” Digital Spy, 22 Sept. 2022, http://www.digitalspy.com/tv/ustv/a41314856/heartbreak-high-autistic-queer-representation.

Frankly TV. Chloe Hayden on Crafting Her Heartbreak High Character. Performance by Fran Kelly, ABC TV, YouTube, 14 Oct. 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQYCO6VFXKE.

McCrossin, Robert. “Finding the True Number of Females with Autistic Spectrum Disorder by Estimating the Biases in Initial Recognition and Clinical Diagnosis.” Children, vol. 9, no. 2, 2022, p. 272., https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020272.

Miller, Ryan A. “My Voice Is Definitely Strongest in Online Communities’: Students Using Social Media for Queer and Disability Identity-Making.” Journal of College Student Development, vol. 58, no. 4, 2017, pp. 509–25. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0040.

Molina-Quzmán, Isabel, and Lisa Marie Cacho. “Historically Mapping Contemporary Intersectional Feminist Media Studies.” The Routledge Companion to Media & Gender, edited by Cynthia Carter et al., 2015, pp. 71-80. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203066911.ch6.

“A Poignant Moment for Neurodivergent Folk Everywhere.” Edited by Marie Claire, Chloé Hayden’s Moving Acceptance Speech at Marie Claire’s Woman of the Year Awards, Marie Claire, 10 Nov. 2022, https://www.marieclaire.com.au/chloe-hayden-rising-star-award-acceptance-speech.

Tharian, Priyanka Rebecca, et al. “Characters with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fiction: Where Are the Women and Girls?” Advances in Autism, vol. 5, no. 1, Emerald, Mar. 2019, pp. 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/aia-09-2018-0037.

—

Ileana Oeschger is a Kalamazoo College student graduating in 2024 with a BA in Psychology and Studio Art. She enjoys highlighting disabled and queer identities in her academic writing and using an intersectional lens to inform her analyses.

You must be logged in to post a comment.