Swifties Make Sense of the Pandemic: Illuminating Pandemic Themes in iTunes Reviews of Taylor Swift’s folklore

Swifties Make Sense of the Pandemic: Illuminating Pandemic Themes in iTunes Reviews of Taylor Swift’s folklore

by Sarah Katherine Wagoner

Introduction with Literature Review

The social distancing and stay-at-home orders of 2020 and 2021 resulting from the coronavirus pandemic complicated and narrowed the number of cultural events that could define the era. We have seen a wavering in the ability of many commonly relied upon fields to sustain normal functioning, like sports, graduation ceremonies, and even normal workplace operations, but music has persisted even through the changes. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry’s “Global Music Report 2021” found that “global music sales grew for the sixth consecutive year in 2020, with total revenues rising 7.4% to $21.6 billion” (Smirke and Barrionnuevo 1). Such a flourishing field presents a unique space for analysis and discourse, especially in regard to the current worldwide themes that have emerged or been illuminated during the pandemic, including the emphasis on nature and imagery. A unique case of such themes being highlighted within pandemic-released music is that of Taylor Swift’s folklore album. Released without much notice on July 24, 2020, many were surprised. The album, which Will Richards describes in NME as having taken a turn from previously pop-centric production to “simpler, softer melodies and wistful instrumentation” became even more significant a topic of analysis when it was awarded “Album of the Year” at the 2021 Grammy Awards (5). It further distanced itself from the pack in terms of impressive sales and streams. Sisario found that as of the end of October 2020, “only a single album has crossed the million-sales mark” during 2020, and that was Swift’s folklore, having “26 million streams, and 57,000 copies” sold the previous October week alone (1). Amid acknowledging the success of Swift’s album, however, it is also important to note the privilege she had to continue recording and promoting her music during a time when many independent artists were unable to secure studio time or the resources to do so. Such factors limit the music available for listeners to buy and support. Having made this acknowledgement, such a release as Swift’s amid a year of crises and uncertainty takes on a new level of meaning and impact in that it has the potential to represent an era of both music and life by people currently experiencing the pandemic and those who will look back on this historical time in retrospect in hopes of better understanding the times.

In order to understand the impact of such a collection of music as folklore, it is very telling to look at how consumers are experiencing, describing, and rating the album because they help to determine the sales, success, and legacy of a musical work. However, it is similarly important to point out that sales do not necessarily align with consumers purchasing what they like/what they deem to be “good” music, but may rely at least in part upon what is available at the time. With this limitation in mind, a qualitative analysis of consumer reviews on an award-winning, era-defining album could be very useful to future musicians and producers who are looking to emulate the ingredients of success that Swift leaned on within the album and the listeners’ response to them. Further, it also would be beneficial for researchers in the future who are looking to mine through the 2020 pandemic year for cultural trends, ideals, and coping mechanisms that rose to the surface of the art.

Previous research has focused on consumer reviews and the themes addressed within those reviews that motivate people to write them. Bansal and Srivastava discuss the affordances of analyzing consumer reviews through the lens of sentiment analysis, finding that it has proven useful in identifying solutions in “marketing, political campaigns, election monitoring, financial predictions and other important tasks” (117). This strategy helps to categorize the reviews people leave in terms of their explanation for their review and paralleling feelings about the product, like if someone chose the battery life or price as reason to review a technology, and then whether that feature led to positive or negative feelings for them (Bansal and Srivastava 117-118). Similarly, in terms of exploring reasoning behind reviews, but different in its focused perspective centering on the reviewed rather than the reviewer, is Li et al.’s contribution to the discourse. They find that in the realm of hospitality and hotel business, since negative reviews are typically unavoidable, that the approach taken to respond to these reviews is noteworthy. They reveal that “85% of TripAdvisor users are more likely to book a hotel that responds to reviews, and 65% agree that a thoughtful MR [managerial response] to a negative review improves the impression” (Li et al. 1). Although musicians typically do not go through consumer reviews to respond to them as hotels might, they may still find value in addressing such consumer grievances in future works, or other artists may see concerns raised and adapt their own work accordingly. Li et al. also offer a unique idea in separating the motivation for negative reviews into the precursors of anger and anxiety rather than assuming all negative feelings are similar enough to group together (3).

Moving closer to my study’s focus of popular music, other research has explored the concepts of image and branding as themes emerging from fans’ reviews. Vannini looks at the way fans of pop star Avril Lavigne credit her authenticity and aesthetic for their admiration of her. This was even more of an interesting discussion at the time because the realization was just being made that “reviewing is no longer confined to interpreting just the sound but now includes various aspects of a multimodal performance that is as much aural as it is visual. These factors have given birth to the amateur (or consumer) reviewer” (Vannini 51). Such revelations have paved the way for more in-depth analyses of the way that aesthetics and paralleling culture impact musical artists’ success and following, as in the case of Swift.

Most closely related to my study is Kim and Hovy’s argument for the importance of reasoning in customer reviews. They posit that merely having “found 189 positive reviews and 65 negative reviews may not fully satisfy the information needs of different users” (Kim and Hovy 483). Although they analyzed manufacturer and restaurant reviews to show the significance of and variety of themes of reasons customers had a positive or negative experience, many of the same principles could apply to a discussion about the consumption of music and the reasons why listeners especially liked or disliked specific content.

Still to be studied is the way that explanations within music consumer reviews can illuminate themes of current events like the coronavirus pandemic. Analyzing listeners’ reviews of an album like Taylor Swift’s folklore to determine the reasoning behind why positive or negative feelings are experienced can bridge a connection between these previous studies’ foci. Previous research has explored sentiment analysis and internal motivations for leaving reviews, the impact of organizations responding to reviews, the potential negative emotions that lead to reviews, and even how reviews can reveal the specific aspects of stars that attract fans to them. However, what this study aims to do is complicate the discussion of how the reviews of an era-defining album, like Swift’s folklore, presents the opportunity to identify and dissect trends of the pandemic most at the forefront of the public’s mind at their time of writing.

Methods

In order to construct my corpus of discourse, I first had to decide from which of the many platforms that Taylor Swift releases her music to pull the reviews. I found that iTunes reviews offered the most appropriate forum of data here, as it consisted of those interested enough to consider actually spending money on the album rather than those who would prefer to stream the songs for free on YouTube or Spotify. Of course, this narrowed down the possible reviewers, but its affordance of exposing reviewers to the album in its entirety, as the iTunes page allows, was worth this.

Further, I analyzed the written reviews of Swift’s folklore (deluxe version) which was released August 18, 2020, about three weeks after the release of the standard version on July 24, 2020. This was an important distinction in my corpus because it eliminated those reviews whose purpose is to be among the first to comment when a new album is released. Such reviews may have skewed my analysis because they could have been written based only off Swift’s previous work and those reviewers’ opinions of that previous work rather than allowing listening time to fully shape and define the reviewers’ opinions of the new album. Instead, focusing on the album version that was released weeks afterwards, reviewers have had plenty of time to listen to all or as many songs as they would have liked and formulate substantiated opinions before having the chance to leave their reviews. Therefore, I did not find reason to eliminate any of the earliest reviews from my corpus based on the deluxe version.

Instead, I set my corpus boundaries to include all the written iTunes reviews of folklore (deluxe) from its release on August 18, 2020 through to the day the album was awarded Album of the Year at the 2021 Grammy Awards on March 14, 2021. This cut-off point was established in order to prevent any biasing in reviewer opinions that could have stemmed from the album being deemed especially successful by this third-party organization. Such constraints curated a corpus consisting of 217 written reviews (I did not consider the ratings where only a star from one to five was awarded because no rationale for those reviews was provided and iTunes would not allow for these to be organized by date, but only showed the total number of ratings and the average star rating. Therefore, I could not filter the star ratings to include only the data from my corpus’ timeframe).

The method of analysis began by first familiarizing myself with the data, reading fully through the list of reviews a few times. In order to solidify the data for future reference, I snapshotted the reviews by scrolling through and taking photos of each grouping that would fit on screen at a time, as iTunes is not programmed to allow printing of review pages. As I familiarized myself with the material, categories emerged from the reviewers’ explanations for their positive or negative experiences of the album that I would later use for coding.

I first sorted through the reviews to separate the positive ones from the negative ones. From those groups, I further sorted to determine the percentage amounts of positive and negative reviews that included explanations for those stances versus those that gave no concrete justification. Another noteworthy coding strategy in determining the impact on perception of the pandemic themes surrounding the album’s discourse was to sort the positive reviews by the overarching reason for the positive perception by the reviewer. Finally, I sorted through the negative reviews to determine the categories of reasons for those sentiments.

Results and Discussion

In sorting through the reviews, the distinction between positive and negative reviews was an obvious first step. In some cases, I referred to the star rating, 1 to 5 that the reviewer assigned the album alongside their written review because of the ambiguity of their sentiment. However, in most cases, the positive or negative experience of the reviewer was made clear within their words. I found that of the 217 written reviews, 179 were positive and 34 were mainly or completely negative reviews. A small number of the reviews (only 4) within the corpus were written in another language besides English, and since this was such a small percentage of the sample, I will not discuss them.

An interesting finding in analyzing the positive versus negative reviews was the amount of reviewers who offered concrete reasonings for their opinions versus those who did not. Some reviewers detailed specific qualities of the songwriting, price point of the album, or other tangible aspect that led them to their formed conclusions.

Other reviewers, however, revealed only their conclusion, often in the form of an adjective describing the album, but we are left with no way of determining how such conclusions were reached or what factors led to the decision. Perhaps this indicates the increased urgency they felt in writing, that their feelings were so strong they felt as if their reviews would better reflect such strength in resonance of emotion through fewer, more concise words. Also, it may reflect their increased desire for others to read their strong opinions, realizing that shorter, more vague reviews may resonate more with other reviewers and elicit likes.

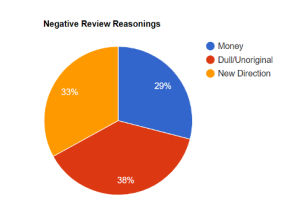

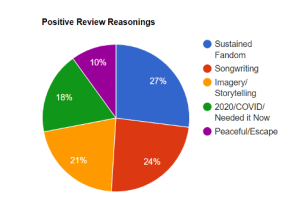

I found that six main categories emerged as prevalent among the positive reviews including those of sustained fandom, Swift’s songwriting, Swift’s imagery/storytelling, reference to COVID/2020/needing it during times like these, peaceful escape, and those reviews that gave no reasoning. In sorting through the negative reviews to determine the categories of reasons for those sentiments, I found four main categories of money requirements, dull/unoriginal content, reference to Swift’s new musical direction/they used to like her more, and those reviews that offered no reasoning.

Of the written reviews, 41% were positive reviews with explanations for those opinions, 40% were positive reviews with no tangible evidence of explanation, 8% were negative reviews with explanation for their reasoning, and 7% were negative reviews with no explanation of reasoning. These findings were significant because they show that very similar percentages of both positive and negative reviewers felt motivated to explain their reasoning as compared to those who relied solely on nondescriptive adjectives of their experience. This may indicate a similar tendency in regard to how people understand and communicate other experiences, including those like the pandemic. Perhaps a similar percentage of people understand cultural eras based mainly off their emotional reactions and feelings while a fairly equal group understands through logic and analytical descriptions of events.

Of the written reviews, 41% were positive reviews with explanations for those opinions, 40% were positive reviews with no tangible evidence of explanation, 8% were negative reviews with explanation for their reasoning, and 7% were negative reviews with no explanation of reasoning. These findings were significant because they show that very similar percentages of both positive and negative reviewers felt motivated to explain their reasoning as compared to those who relied solely on nondescriptive adjectives of their experience. This may indicate a similar tendency in regard to how people understand and communicate other experiences, including those like the pandemic. Perhaps a similar percentage of people understand cultural eras based mainly off their emotional reactions and feelings while a fairly equal group understands through logic and analytical descriptions of events.

Beyond simply categorizing between positive and negative sentiments of the reviews, another interesting and revealing analysis was the coding of explanation of those positive and negative reviewers who chose to include reasonings. Of the negative reviews that offered explanation, 29% referenced money as being the main issues (for instance that adding only one song and marketing the album as deluxe was something to take offense to), 38% claimed that the album was dull or unoriginal, and 33% were unhappy with Swift’s new alternative musical direction and liked her more in past eras. It makes sense that themes like stress or resistance to change would emerge at the forefront of reviewers’ minds during the pandemic. Especially as many people are eagerly awaiting a return to “normal” life, or what they remember that to be from pre-pandemic times, such clinging to past musical eras is a logical resulting thought process. Similarly, financial strains are relevant as many people have recently lost their jobs or experienced economic hardships due to the pandemic.

Beyond simply categorizing between positive and negative sentiments of the reviews, another interesting and revealing analysis was the coding of explanation of those positive and negative reviewers who chose to include reasonings. Of the negative reviews that offered explanation, 29% referenced money as being the main issues (for instance that adding only one song and marketing the album as deluxe was something to take offense to), 38% claimed that the album was dull or unoriginal, and 33% were unhappy with Swift’s new alternative musical direction and liked her more in past eras. It makes sense that themes like stress or resistance to change would emerge at the forefront of reviewers’ minds during the pandemic. Especially as many people are eagerly awaiting a return to “normal” life, or what they remember that to be from pre-pandemic times, such clinging to past musical eras is a logical resulting thought process. Similarly, financial strains are relevant as many people have recently lost their jobs or experienced economic hardships due to the pandemic.

I found that of the positive reviews that offered explanations, 27% were explained by sustained fandom of Swift, 24% were credited to Swift’s songwriting, 21% focused on Swift’s imagery/storytelling skill, 18% were reference to 2020/COVID/the feeling that the album was especially needed at the moment, and 10% revolved around the peacefulness and opportunity for escape from the world they experienced when listening. Such findings were particularly noteworthy because of the significant percentage of explanations credited to 2020, COVID, the escape the album provides, and the pull of the imagery and storytelling. Cloake writes about how amid the 2020 year, his travel book “read like a fantasy of the wildest sort. I can almost feel the weight of the warm summer evening settle over my cramped London flat. With my world shrunk to the limits of an all-too-familiar horizon, I’ve rediscovered the vicarious pleasures of armchair travel” (1). I expect that the escapism and imagery references within the reviews indicate that this vicarious experience that Swift provides through her music, and even her nature-themed visual aesthetics of the album, as Cloake experienced reading travel guides, has been a particular comfort for listeners during the pandemic and offered a means of travel when travel was not possible. Even Swift herself described how “the lines between fantasy and reality blur and the boundaries between truth and fiction become almost indiscernible” in her album (Richards 3). Identifying such trends may point toward popular coping strategies of dealing with the stress of the times that people turned to as they relied on music, especially music like folklore that embodies this escapism and hope for the future during the pandemic. This may prove to be a significant finding as researchers attempt to make sense of how people dealt with the pandemic and will cope with future crises.

I found that of the positive reviews that offered explanations, 27% were explained by sustained fandom of Swift, 24% were credited to Swift’s songwriting, 21% focused on Swift’s imagery/storytelling skill, 18% were reference to 2020/COVID/the feeling that the album was especially needed at the moment, and 10% revolved around the peacefulness and opportunity for escape from the world they experienced when listening. Such findings were particularly noteworthy because of the significant percentage of explanations credited to 2020, COVID, the escape the album provides, and the pull of the imagery and storytelling. Cloake writes about how amid the 2020 year, his travel book “read like a fantasy of the wildest sort. I can almost feel the weight of the warm summer evening settle over my cramped London flat. With my world shrunk to the limits of an all-too-familiar horizon, I’ve rediscovered the vicarious pleasures of armchair travel” (1). I expect that the escapism and imagery references within the reviews indicate that this vicarious experience that Swift provides through her music, and even her nature-themed visual aesthetics of the album, as Cloake experienced reading travel guides, has been a particular comfort for listeners during the pandemic and offered a means of travel when travel was not possible. Even Swift herself described how “the lines between fantasy and reality blur and the boundaries between truth and fiction become almost indiscernible” in her album (Richards 3). Identifying such trends may point toward popular coping strategies of dealing with the stress of the times that people turned to as they relied on music, especially music like folklore that embodies this escapism and hope for the future during the pandemic. This may prove to be a significant finding as researchers attempt to make sense of how people dealt with the pandemic and will cope with future crises.

Conclusion

The old cliché, “Art imitates life” may come to mind when seeing the illuminated pandemic themes that reviewers present within their feedback on Taylor Swift’s folklore (deluxe version) album. However, this also leads to one of the limitations of this study in that it is especially difficult in analyses like this to determine whether the reviews were completely justified in their perceived praises and offenses and whether these pandemic themes would have been so clearly emerging if reviewers were listening to the album in another year. However, for me, this is the value in analysis. The perceptions of the reviewers and their tendencies to relate the album to the current worldwide situation exemplifies the entanglement of art and life amid historical times. I expect that these mutual dependencies will be a contributing factor to the longevity of success of Swift’s folklore album and the sustained listener correlation with the pandemic era. Other limitations with the study include the condensed timeframe of analysis, as other trends may have emerged from more prolonged examination of the corpus, and the fact that reviews from folklore (deluxe version) were analyzed rather than those from the original version which potentially could have produced different results. Possible directions for related future research include a coding theme analysis of the originally released version, analyses of other era-defining albums amid past and future crises and historical eras to see if trends of the times emerge within them as well, and also another analysis of Swift’s album in a few years to see whether the reviewers’ pandemic-related interpretations still stand. Overall, further focus on this exploration of the correlations between art, specifically music, and historical eras may help people to better understand and cope with their feelings during particularly emotionally-charged times.

Works Cited

Bandal, Barkha, and Sangeet Srivastava. “Aspect Context Aware Sentiment Classification of Online Consumer Reviews.” Information Discovery and Delivery, vol. 48, no. 3, 2020, pp. 117-128.

Cloake, Felicity. “Trapped at Home with no Hope of Dining Out, I’ve Rediscovered the Vicarious Pleasures of Armchair Travel: From My Cramped London Flat, I have been from the Hook of Holland to the Golden Horn, and Across the Himalayas.” New Statesman (1996), vol. 149, no. 5518, 2020.

Kim, Soo-Min, and Eduard Hovy. “Automatic Identification of Pro and Con Reasons in Online Reviews.” Proceedings of the COLING/ACL 2006 Main Conference Poster Sessions, 2006, pp. 483-490.

Li, Chunyu, Geng Cui, and Yongfu He. “The Role of Explanations and Metadiscourse in Management Responses to Anger-Reviews Versus Anxiety-Reviews: The Mediation of Sense-Making.” International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 89, 2020, pp. 102560.

Richards, Will. “Read Taylor Swift’s New Personal Essay Explaining Eighth Album ‘Folklore’.” NME, 2020, www.nme.com/news/music/read-taylor-swift-new-personal-essay-explaining-eighth-album-folklore-2714540.

Sisario, Ben. “Taylor Swift Returns to No. 1 as ‘Folklore’ Sales Pass 1 Million.” The New York Times, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/26/arts/music/taylor-swift-folklore-million-sales.html.

Smirke, Richard, and Alexei Barrionuevo. “IFPI Global Report 2021: Music Revenues Rise for Sixth Straight Year to $21.6B.” Billboard, 2021, https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/9544722/ifpi-global-report-2021-music-streaming-sales-revenue-pandemic/.

Vannini, Phillip. “The Meanings of a Star: Interpreting Music Fans’ Reviews.” Symbolic Interaction, vol. 27, no. 1, 2004, pp. 47-69.

—

Sarah Katherine Wagoner graduated with degrees in English and Communication from North Carolina State University in May 2021. This article was written during the spring semester of her senior year. In the fall of 2021, Sarah began her MA in English at NC State with a concentration in Rhetoric and Composition. During her time in the program, she will work as a Graduate Teaching Assistant in the First-Year Writing Program while also working toward a certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. Sarah hopes to pursue a career in English and writing instruction at a North Carolina community college after graduation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.