back to 5.2

The Electronic Outcry: Conceptualizing Social Media Impacts in the Palestinian Conflict

The Electronic Outcry: Conceptualizing Social Media Impacts in the Palestinian Conflict

by Laith Shehadeh

1948: the year which some celebrate and others mourn the creation of the State of Israel. Ever since the proclamation of a Jewish state, there has been never-ending conflict in the area that some refer to as Israel and others refer to as Palestine. This segment of land is religiously significant to Jews, Christians, and Muslims, and as a result, control over several holy sites and cities has been an ongoing struggle since Israel’s establishment. While tensions remained high for the following two decades, armed conflict was minimal. However, in 1967, things took a turn for the worse during the Six-Day War, when Israel annexed the Golan Heights (contested South-Syrian Land) and launched a full-scale occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (If Americans Knew). To this day, the occupation of the West Bank and blockade of Gaza remain, where Israel has allegedly committed a multitude of human rights violations, according to the United Nations (If Americans Knew). For decades, criticism of Israel in the Western World was typically met with harsh rebuke, as a result of religious norms and the influence of the Jewish Lobby in Washington, D.C. Typically, leaders who expressed opposition towards Israel would be characterized in the media as anti-Semitic and authoritarian. However, in a world where information can travel anywhere in the flash of a second, the dynamic has changed. The effects of social media cannot be ignored, as their influence in the last two armed conflicts has been significant. The power of the hashtag and “clicktivism” has led to the coining of terms such as #BDS (Boycott, Divest, Sanction). Activists are redefining and modernizing terms like #FreePalestine and #BoycottIsrael. Palestine’s struggle for liberation has become rhetorically clarified due in large part to social media: the hashtag #FreePalestine allows users to share, analyze, and respond to information and images that directly engage both activists and opponents. This form of electronic diplomacy has shifted the political narrative, one where facts and emotions are almost always intertwined and Israel’s actions do not go unquestioned.

While the intent of the Free Palestine Movement is a given, analyzing their channels of communication and information exchange, in addition to Pro-Palestinian Solidarity with other social movements will be the primary motive of this inquiry. Before I get started, I’d like to make it clear where I stand in this conflict, I am a very strong supporter of the Palestinian Liberation. Both my parents immigrated to the United States in the early 1990s from Palestine, where they were born, raised, and educated. While my parents lived in the US, all my family remained scattered throughout Middle East. I often traveled to Palestine to visit my family. Frequent, lengthy visits allowed me to retain dual citizenship, and maintain fluency in the Arabic language. It would be false to say that my immersion in my Palestinian heritage has not influenced my stance on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Nonetheless, I remain committed to facts and learning more about the conflict by utilizing diverse news sources, constantly fact-checking what is broadcasted on mainstream media, and conducting primary research to solidify my stance. My bias on the conflict will likely be displayed often, but it is unavoidable as I will be citing my personal experiences that have inspired me to remain committed to the liberation of my people.

A key distinction of social media, and Twitter especially, from previous information outlets is its availability and ability to share information from primary sources with the rest of the world, or as Eugenia Siapera states in her article “Tweeting #Palestine: Twitter and the Mediation of Palestine,” Twitter use has precipitated “a redistribution of power from fact-based hard news and information produced by mainstream, branded media to diffused networks of news producers, who tweet during real-time events as they witness or participate in them, or who tweet their opinions and reactions to these events” (n. pag.). The rise of social media has to some extent open-sourced political journalism, where facts and emotion intertwine to allow the sharing of news alongside opinions like never before.

In December of 2008, millions watched live as Israel launched Operation Cast Lead, its largest military escalation with Hamas, the armed resistance force of Gaza, since 2006 (Institute for Middle East Understanding). In past conflicts, international outcry was often ignored or muffled. However, Twitter was used in such an incendiary fashion, spurring a large international outcry, that Operation Cast Lead became the first conflict between Israel and the Palestinian Resistance where a public outcry impacted the outcome by shortening length of the conflict. When the Israeli Army was accused of using white phosphorus, an incendiary weapon condemned by the Human Rights Watch and the United Nations, on dense civilian populations in Gaza, users like Zaynep Alp (see fig. 1) sought to uncover and share this disturbing information. The convenient access and speed of transmission of Twitter led to a new phenomenon: the ease of outrage. Zaynep’s tweet was composed of both emotion and fact, as the Israelis were referred to as “the occupation,” and very little information was given about the conflict or the victim. Tweets like Zaynep’s aim to outrage fellow supporters of the Palestinian Resistance so that other users can compile and redistribute this information in more comprehensive tweets.

Since 2001, If Americans Knew, an “independent research and information-dissemination institute”, has been conducting and publishing research regarding fatalities in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, exact dollar amounts of US military aid to Israel, and all other relevant data. In recent years, If Americans Knew’s page views have soared due to the fact that the institute’s literature is linked or quoted in tweets. Their infographics can be easily copied and tweeted as well. Outraged Twitter users, like Zeynep Alp, could employ the hashtag #gaza for the purpose of content aggregation, and #freePalestine to spread the liberation’s message (see fig. 2 & fig. 3). As #gaza was trending in early January 2009, it would prove effective to use the hashtag to inform users about related information, copied from If Americans Knew’s website as they searched updates about the war.

- Fig. 2. Zeynep Alp’s tweet.

- Fig. 3. Zeynep Alp’s tweet.

These hashtags provided a multitude of users, sharing opinions and facts, a place to convene in one virtual location, where they could network, debate, and learn. This served as a pivotal moment for the Free Palestine movement, as social media sites that are accessed by millions of users are significantly more difficult to censor and control than traditional media platforms. Compared to previous armed conflicts such as the Second Intifada, the Israeli government faced a completely different type of criticism: the viral, international condemnation on social media. Suddenly the public could be aware of facts or images critical to conflicts within seconds, rather than wait for major news outlets to verify, sanitize and publish grave information. Because the news was presented in such a blunt manner, Israel faced scrutiny that led Operation Cast Lead to end within three weeks, significantly shorter than the previous two-month conflict in 2006 (IMEU 13). The next Israeli-Palestinian conflict began November 14, 2012. Operation Pillar of Defense, an intensive airstrike campaign, killing thousands of civilians, in response to Hamas’ rocket fire at Israel’s southern border (“Israel-Gaza Violence” n. pag.). By this time, according to Internet Live Stats, an average of 340 million tweets were being sent out daily, as compared to the 2.5 million tweets per day in 2009 (n. pag.). As a result of the exponential increase in Twitter users, social media outrage was on the rise, and the hashtags #FreePalestine and #Gaza were swarming most Twitter feeds. Images of the bloodshed spread, and emotional tweets called for an end to the killing (see fig. 4).

Twitter user Adilca Rodrigues shared an image of four Palestinian children who were killed as a result of the Israeli airstrikes. What followed after images like this one made it to Twitter was a harsh blow to the legitimacy of the Israeli air campaign. Although instances like this, where children are killed as a result of shelling, were not uncommon prior to 2012, the easy access to information was certainly unprecedented, provoking emotions across the political spectrum. As a result of the criticism Israel faced (in addition to the ineffectiveness of their air campaign), Israel ended Operation Pillar of Defense only seven days later, on the 21st of November, 2012 (“Israel-Gaza Violence” n. pag.).

Citizen-journalists were also impacting the reaction to the conflict. Sarah Ismail’s tweets about the pro-Palestinian protest in San Francisco are far more passionate than standard journalistic style allows, but she basically reports on the demonstration. Rather than saying “Large Pro-Palestinian protest in San Francisco,” as a traditional reporter would, Ismail uses words like “we” to align herself with the movement and call for others to join her in “taking over the streets” (see fig. 5). The content seemed journalistic in nature, but the “reporters” in this case made no pretense of objectivity. Because citizen-journalists/Twitter users are sometimes the only ones covering these events due to the mainstream media embargo on news about Israel that might be perceived as negative. Twitter serves to fill the news void about these events, and it cannot be sanitized.

Across the world, people were able to rally together and call for action through using the hashtags #FreePalestine and #Gaza. As seen in figure 6, no borders could stop the wave of criticism that Israel faced as a result of their bombing campaign. Massive protests across the globe condemning Israel’s actions, like the one seen here in Athens, Greece, demonstrated that the world was finally paying attention.

The #FreePalestine movement, by virtue of the hashtag and its prominence on Twitter, has formed unusual coalitions with other activist discourse communities. For instance, the Neturei Karta, a group of Ultra-Orthodox Jews, have aligned themselves with the #FreePalestine movement. The Neturei Karta have come under harsh criticism for their support, yet they remained determined to work towards peace. At most large demonstrations, and even the annual AMP (American Muslims for Palestine) Conference, Neturei Karta is present (see fig. 7). In the past decade, the alliance between Neterui Karta and the #FreePalestine movement has attracted great controversy, as most Zionists consider the Neterui Karta traitors for “opposing the livelihood of their own brothers” in that they oppose Jewish settlements in Gaza. Neterui Karta’s embrace of #FreePalestine is quite unique: conflicts that are surrounded by religious and social divides rarely produce alliances like this one. Additionally, Neterui Karta’s activism on social media has helped increase the influence of the #FreePalestine movement across all platforms. Their unique alliance has allowed the exchange information, photos, retweets, and data, while also breaking down the ideological barriers that commonly pit groups at odds.

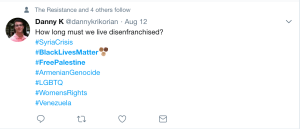

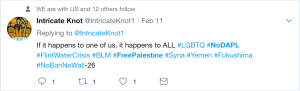

While the Neterui Karta alliance has broken down long-held political and religious barriers between social justice activists, the #FreePalestine movement has gained validity and recognition by forming informal coalitions with other emerging social justice groups. By including hashtags from such groups as #BlackLivesMatter and #NoDakotaAccessPipeline (see fig. 8), Palestine activists emphasize the racial and even environmental justice missions that these two movements share with them, and seek to engage North American activists, where support has traditionally strong for Israel.

At first glance, such a relationship seems odd, since the groups are geographically separated and involved in very different struggles. But on closer examination, the movements actually have a lot in common. Because the #NoDakotaAccessPipeline and #IdleNoMore communities advocate for indigenous land rights for Native Americans and Canada’s First Nations, the solidarity with #FreePalestine emphasizes their shared dispossession. The shared fight for land and resources becomes evident immediately with the juxtapositioning of the hashtags. Similarly, #BlackLivesMatter has swept the internet and has brought significant attention to police brutality and racial injustice in the United States. By posting #FreePalestine and #BlackLivesMatter tags together, the struggle for racial justice for African Americans and fair treatment for Palestinians de-localizes the movements, and shifts the discourse towards a discussion about abuses of power everywhere (see fig. 9 and 10). The willingness to support nascent social justice movements garners the #FreePalestine movement more supporters.

- Fig. 9. Intersectionality.

- Fig. 10. Intersectionality.

Twitter has become a place for protests and activism, seemingly safer than “real” spaces. However, the threat of censorship and exile remains present, as there have been allegations against Twitter and Facebook for censoring anything they deem Anti-Semitic, which in turn can be easily spun as a tactic to further delegitimize the work of activists. The line of free speech on social media and what can be deemed “offensive” is extremely difficult to draw. This grey area has been one of the largest challenges facing the #FreePalestine discourse community, as social media propagates the idea as a common place for the free flow of new ideas and information, yet in reality, private entities do own all social media platforms. Palestinian activist groups have been subject to suppression and deletion of Facebook and Twitter posts, while Pro-Israeli pages have had far less censorship or suppression. Violation of vague ‘community guidelines’ have been the excuse to shut down several activist pages, bringing up the question of free speech on social media. Alex Mills in “The Law Applicable to Cross-Border Defamation on Social Media” examines Facebook’s particularly uneven and harsh policy, noting that:

Facebook’s somewhat notorious censorship policy is perhaps the best-known example of this. […] Tellingly, Facebook’s policy is described as a set of “Community Standards” which “aim to find the right balance between giving people a place to express themselves and promoting a welcoming and safe environment for everyone” – replicating the function of national law rather than referring or deferring to it. A prominent non-governmental organization focused on the rights of Internet users has expressed the concern that “Facebook has become a sort of parallel justice with its own rules that we cannot fully understand.” This has led some to refer to Facebook as “Facebookistan” – a self-governing community (with a population of monthly active users approximately equal to the population of China) which is deterritorialised but otherwise potentially comparable to a state. (Mills 31-32)

Like many discourse communities, the #FreePalestine movement is one that is currently in the process of developing strategies in order to cope with the censorship and the fact that social media platforms have their own agendas, which may not always align with the principles of free speech and a free flow of ideas and information. As different platforms of speech and empowerment evolve and reform, opposing narratives and the free flow of information will continue to be more difficult to suppress.

As I mentioned earlier, my involvement in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict dates back since I was born. Frequent visits to the West Bank to visit family resulted in my immersion in two different cultures. Throughout my experiences both inside the West Bank and out, I feel obliged to tie what I have seen with my own eyes into my analysis. Blatant segregation, apartheid, and denial of fundamental human rights are an unfortunate part of day-to-day life for Palestinians. In my own experience, my travels have been limited due to the fact that I am not allowed to drive on “Jewish Only” roads; land belonging to my family for centuries has been stolen to create new, exclusive settlements for Jewish Israelis, and I am no longer allowed to enter the State of Israel simply based upon the color of my Palestinian ID card. I could ramble on for pages about the use of military checkpoints to humiliate Palestinians, but thousands of others have been telling the same stories for decades. What has changed, however, is the motivation surrounding the international community and the methods that they have employed to display such a shift. This shift is unforeseen and often overlooked, and will have eventual long-term social, political, and economic effects on Israeli policy, with the ultimate goal of a peaceful resolution. A fusion of in-person protests, social media activism, and fostering of emerging discourse communities have distinguished the #FreePalestine discourse community as robust and resiliant. When Israel battled Hamas in 2014, I was featured in the Toledo Blade during a protest on a busy Toledo intersection (see fig. 11).

What may have been a small appearance in a local media outlet grew exponentially as I suddenly had friends, who had little to no knowledge on the conflict, contacting me expressing either their support or their desire to learn more about the conflict. What may seem like an isolated incident from my perspective is, in reality, just one of thousands of similar interactions that have transpired as a result of the progression of the #FreePalestine movement. Protests similar to the one I attended have occurred for decades, but through the use of social media, previously uninformed people can express their support and protest virtually, increasing the level of political pressure against the opposition.

While the struggle for Palestinian Liberation may not be new, the social media culture and discourse communities that have arisen as a result of continuous struggle for liberation and cross-political dialogues certainly are. Social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook have enabled not only a new way of exchanging and analyzing information, but they’ve also fostered new relationships and connections that likely would not have arisen without some common platform. In the past seven years, the impact of social media, Twitter specifically, has brought unprecedented scrutiny of Israel and its supporters. This pressure has undoubtedly influenced Israel’s military practices and policies, as there has been an obvious shift in how conflicts have been handled by Israel. While the bloodshed may continue, the eyes of social media activists will remain vigilant, determined to reach their end goal: liberation for the Palestinian people, and all of those that have aligned themselves with their cause.

Works Cited

@anonymousky. “protest in #Athens at moment #solidarity with #gaza #freepalestine” 17 Nov. 2012. 1:29 PM. twitter.com/AnonymouSkY/status/269869964213776385.

@dannykrikorian. “How long must we live disenfranchised?” Twitter, 12 Aug 2017. 12:54 PM. twitter.com/dannykrikorian/status/896414489138143232.

@DeeDovichPoet. “The bodies of four sibling children who were killed in #Gaza today in an Irsaeli Airstrike @TheYoungTurks NSFW.” 18 Nov. 2012, 6:49 PM. twitter.com/DeeDovichPoet/status/270312822372708352.

Hale, Isaac. “Daniel Alhaj, left, and Laith Shehadeh, right, drive by protestors with a Palestinian flag hanging out their window. The Toledo Blade. 25 Jul. 2014.

@intricateknot1. “If it happens to one of us, it happens to ALL.” 11 Feb. 2017, 9:23 PM. twitter.com/IntricateKnot1/status/830603131796885504.

“Israel: White Phosphorus Use Evidence of War Crimes.” Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch, 17 Apr. 2015. Accessed 3 Dec. 2016.

IMEU. “IMEU: Institute for Middle East Understanding.” Operation Cast Lead. January 4, 2012. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016. imeu.org/article/operation-cast-lead.

“Israel-Gaza Violence.” BBC News. BBC, 22 Nov. 2012. Accessed 06 Dec. 2016.

@mamazizi. “occupation spreads gases causing headache and increasing human temperature #gaza.” 9 Jan. 2009, 1:14 PM. twitter.com/mamazizi/status/1107728828.

@mamazizi. “American taxpayers give Israel approximately $7 Million per day #gaza” 9 Jan. 2009, 1:33 PM. twitter.com/mamazizi/status/1109617422.

Mills, Alex. “The Law Applicable to Cross-Border Defamation on Social Media: Whose Law Governs Free Speech in ‘Facebookistan’?” Journal of Media Law, vol. 7, no. 1, July 2015, pp.1-35. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/17577632.2015.1055942.

Neturei Karta International. “Photos of today’s counter protest outside the Israeli Consulate in NYC,” 10 Nov. 2016. http://www.facebook.com/179895388749404/photos/.

@sarzrepublic. “#gaza protest in San Francisco. We took over the streets! #Freepalestine” Twitter, 16 Nov. 2012, 8:31PM. twitter.com/SarzRepublic/status/269613591257300993.

Siapera, Eugenia. “Tweeting #Palestine: Twitter and the Mediation of Palestine.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 17, no. 6, Nov. 2014, pp. 539-555. Doi:10.1177/1367877913503865.

“Twitter Usage Statistics.” Internet Live Stats. Real Time Statistics Project, n.d., http://www.internetlivestats.com. Accessed 11 Nov. 2016.

@US_Campaign. “#SolidarityIs standing with Black Liberation.” Twitter, 11 Aug. 2016, 1:06 PM. twitter.com/US_Campaign/status/763783599443279872.

Weir, Allison. “If Americans Knew Who We Are.” Ifamericansknew.org. If Americans Knew, 1 Feb. 2001. Accessed 03 Dec. 2016.

—

Laith Shehadeh is a junior at the University of Cincinnati studying Operations

Management and Business Economics. His interest in Middle Eastern conflicts and

politics stems from having American-Palestinian Dual Citizenship, in addition to having

traveled to the Middle East several times.

You must be logged in to post a comment.