The Dynamic Symbolism of Clothing in Russian Cinema: An Analysis of Borders and Identity

by Alex D. Luta

In Russian cinema, directors employ the motif of clothing to create and define borders between opposing entities. While the characters in these films symbolize the entities, it is clothing that makes such symbolism evident. The directors of the films Circus, East-West, and The Cuckoo employ clothing to define borders between good and evil, foreign and domestic, and enemy and ally, respectively. In some films clothes are worn by the characters voluntarily, while in others clothing is forced upon characters. Clothing forced upon characters symbolizes an inability to reconcile differences with another, as is the case in East-West and The Cuckoo. In such instances, a shift in clothing style may indicate a “crossing” of the border, but it does not necessarily guarantee subsequent “assimilation.” While the symbolism of clothing remains the same in each film, the theme developed by the directors varies. This theme reflects the nature of clothing as a dynamic symbol that provides directors with the freedom to construct and define borders in a variety of manners.

In the construction and definition of borders, clothing directly relates to the concept of “otherness,” a central aspect of Russian cinema. In films, “otherness” refers to the duality of Russia and the “others,” or outsiders. Such duality helped develop the idea of Russian identity through film. “Otherness” was an important concept in early Russian films, like Circus, which was released in 1936, and is still an important concept in contemporary Russian cinema. Books (Norris & Torlone), film symposia (“White Russian-Black Russian”), and university courses (Fedorova & Sadowska) have all been centered on the concept of “otherness” in Russian cinema. During the Soviet Union and after its collapse, “otherness” has been a significant part of Russian cinema and culture (“White Russian-Black Russian”). Anyone studying Russian history or contemporary Russia should be familiar with this concept so that they can better contextualize what they are studying. Clothing provides an interesting lens through which to study “the other” in these films, as tracking characters’ clothing throughout the films provides insight into how directors view identity.

While previous publications have been written on clothing in Russia and in Russian cinema, I focus here on different aspects of the symbolism of clothing, and I include more recent films in my analysis. In her analysis, Emma Widdis was concerned about films made before 1953, focused on the distinction of “insiders,” and placed greater emphasis on the history of fashion in the Soviet Union. She noted that directors use clothes as a sign of belonging, in later films the nature of Soviet and un-Soviet clothing tends to blur, and the “clear-cut oppositions of belonging and non-belonging begin to break down” (Widdis 51). As these oppositions break down, a new language of clothing emerges that creates a united vision of Sovietness. I take a different approach in my analysis. Two of the films I discuss were made after 1953; I focus instead on the distinction of “outsiders,” and I analyze the construction and nature of the clear opposition between “outsiders” and “insiders.”

In the film Circus, director Grigori Aleksandrov contrasts good and evil through white and black clothing (Circus). The film tracks the flight of circus performer Marion Dixon from the US to the USSR. At the beginning of the film, she is chased by a mob for conceiving a mixed-race baby. As she is fleeing, she is helped aboard a train by a German named Kneishitz. They go together to the USSR, where Marion joins a circus and meets Martinov, the lead male character. In the film the two primary male characters, Martinov and Kneishitz, vie for influence over the protagonist, Marion. Throughout the film, each man wears only one color of clothing. Kneishitz, the evil German villain who exploits Marion’s performing talents for his own profits, is always garbed in black. By contrast, Martinov, the

good hero who tries to liberate Marion from Kneishitz’s vile grip, is always dressed in white. To emphasize the contrast of color between these two characters, Aleksandrov directs a scene in which Martinov, who is inside of a brightly lit room with Marion, glowers through a window at Kneishitz, who is in the freezing darkness of night on the other side of the room’s window. Frost surrounds the perimeter of the window, symbolizing the icy enmity between Martinov and Kneishitz. The brightly lit interior accentuates Martinov’s white clothes, while the dark night accentuates Kneishitz’s black clothes.

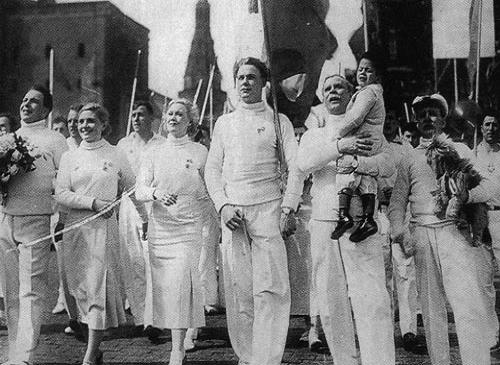

While Aleksandrov utilizes black and white clothing to contrast the good Martinov and evil Kneishitz, he also utilizes it to convey Marion’s crossing from the influence of evil to good. At the start of the film, when Marion is under Kneishitz’s control, she dresses in black clothing and wears a black wig, depicting Kneishitz’s influence over her. As the film progresses and she sides increasingly with Martinov, Marion begins to dress in white attire. During a pivotal scene in the film, Marion stares into a mirror wearing half of her dark wig, exposing half of her natural blond hair. This scene serves to depict Marion’s conflict between choosing Martinov and Kneishitz, Martinov representing the light, natural blonde hair and Kneishitz the black wig. Ultimately, Marion chooses Martinov, and in the final scene of the film she proudly marches and sings with Martinov, her child, and other Russians garbed in white while exposing all of her natural blonde hair.

As shown here, one theme supported by the motif of clothing is the constant struggle between good and evil. Aleksandrov purposefully selects the color of the clothes to be white and black in order to represent good and evil, respectively. Marion’s conflict in choosing between Kneishitz and Martinov, and her ultimate transformation from wearing dark to white clothing, depict a struggle between good

and evil in the film. Because her transformation is successful, another theme is the potential to be purified. Aleksandrov uses clothing to create a border between good and evil, and Marion successfully crosses it toward the influence of good. In this case, clothing is also a hard symbol of identity. Clothing helps to create Aleksandrov’s idealized Soviet identity, one of purity and good. This is exemplified in the film’s final scene, in which the proud Soviets, all dressed in white, march and sing happily in unison.

While Aleksandrov creates a distinction between good and evil through clothing in Circus, in the film East-West (also known as Est-Ouest) director Régis Wargnier creates disparity between the French and Soviet characters through Western and Eastern clothes (East-West). In this film, Russian expatriates who fled the nation after the Bolshevik Revolution return to the USSR in 1946 per Stalin’s invitation. Among them are a doctor, Aleksei Golovin, his wife, Marie, and son, Serioja. Upon arriving in Odessa, many of the expatriates are killed, tortured, or sentenced to forced labor. Soviet officials believe that Marie is a spy, so they beat her and advise Aleksei to divorce her. He remains with his wife, but over the course of the film they grow further apart, and Marie focuses on escaping back to France.

In East-West, clothes serve as a border between foreign and domestic. Upon arriving in Russia, Marie, the protagonist of the film, wears colorful western clothes, distinguishing herself as a foreigner. In order to appear more domestic, and because French clothes are not available, she starts to wear the Soviet style of clothing. She uses clothing as a method of attempted assimilation because the Soviets expect her to wear their particular style of clothing, thereby restraining some of her freedom. The Soviets tend to wear dark and drab clothes, which contrasts her colorful and more elaborate French clothing. At one point in the film, Aleksei purchases a silk dress for Marie, but the dress is gray. Even for more formal occasions, Marie is restricted by the color of her clothing in order to conform to Soviet society and appear more domestic.

A theme developed by the motif of clothing in East-West is the ultimate failure of forced assimilation. Wargnier explicitly chooses Marie’s transformation in clothing style to represent her struggle to assimilate. In order to integrate herself into Soviet society, Marie abandons her Western style of dress for that of the Soviets. While she crosses the border from foreign to domestic, she has not truly assimilated. Although she may dress like the rest of society, cultural and lingual barriers, as well as her will to resist, prevent her from true assimilation. Her Soviet clothes are only a mask that obscure her origins, but do not fully suppress them. Clothes are still a significant part of a culture, however. Marie chooses to wear French shoes while escaping to the French embassy in Bulgaria, but her Soviet stockings alarm a Bulgarian guard, and she is almost caught. In this scene, Marie is half Western and half Soviet, which reinforces her failure to fully integrate into the Soviet culture as a result of forced assimilation through clothing.

While in Circus, there is a clear border that Marion crosses to directly assimilate, in East-West, this border is superficial. Marie crosses the border by wearing Soviet clothes and becoming domestic, but this crossing does not go to the core of her identity. In this film Marie is still French at heart, and the clothes are but a thin mask hiding her true identity. Unlike Aleksandrov, Wargnier does not create a hard symbol of identity through clothing. In doing so, he is able to emphasize other factors of identity, such as language and culture. He is also able to treat identity as a more enduring quality than in Circus, in which Aleksandrov implies that Marion’s white clothes allowed her to become a patriotic Soviet marching with the rest.

While the directors of the aforementioned films have used clothing to distinguish good from evil and foreign from domestic, in the film The Cuckoo director Aleksandr Rogozhkin uses uniforms of opposing nations at war to symbolize the enemy (The Cuckoo). This film is set during World War II, and it begins with a Finnish sniper being chained to a rock by German soldiers.

The sniper’s name is Veikko, and against his will, he is dressed in an SS uniform and ordered by the German soldiers to shoot as many Russian soldiers as he can. The German soldiers leave him alone, chained to the rock. The film also introduces Ivan, a Russian soldier who travels with a convoy that is blown up. He escapes and finds a Saami woman, Anni, who treats his injuries. Veikko manages to escape and find Anni’s home. Ivan becomes aggressive upon seeing Veikko’s uniform, but over the course of the film they come to understand each other and get along.

Although Veikko becomes a pacifist, because of his preconceptions Ivan treats Veikko with disgust and even attempts to kill him. Both are decent people forced to wear uniforms that do not accurately represent them, which creates tension between the two. The separation between the characters by uniform and their interactions suggest a potential interpretation of clothing as a symbolic barrier. Anni, who wears the traditional clothing of the Saami people, brings both of the soldiers into her home. Over the course of the film she tries to reconcile the two, who are separated by the misleading barrier caused by the uniforms imposed upon them. At the end, when Veikko and Ivan are at peace with one another, they are also both wearing traditional Saami clothing made for them by Anni, symbolizing their unity.

A theme supported by the motif of clothing in the film is that clothing serves as a border between cultures. The misunderstanding between the characters is a result of language, culture, and clothing, the latter of which sparks Ivan’s ire. The characters are not able to communicate properly and share in cultural traditions properly, such as Veikko’s Finnish sauna and Ivan’s Russian mushroom picking. Even with these discrepancies, once everyone is dressed the same at the end, they reach an understanding regardless of language or culture. Once they are all dressed alike, the barrier between them is torn down and they become allies.

In The Cuckoo, Rogozhkin employs clothing to create an artificial border between the characters. Ivan becomes aggressive upon seeing Veikko’s uniform, but his aggression is unjustified, as at heart, Veikko is a kind pacifist who has great potential to get along with Ivan. The uniforms they wear symbolize the opposing militaries in the war, but that has little to do with these characters as individuals. The clothes are forced upon the characters, and they create an artificial identity for each. With the help of Anni’s reconciliation, both characters cross a border into mutual territory by wearing Saami clothing. Rogozhkin uses clothing to explore different aspects of identity. He shows that national identity is just one part of the overall identity, and is not necessarily representative of the individual. Despite different nationalities, languages, hobbies, and attitudes, all of the characters are able to understand each other by the end of the film. Through this result, Rogozhkin testifies to the universal human identity we all share, one that allows us to put aside differences in order to come together.

Although clothes define borders in Russian cinema, these borders may be crossed, destroyed, or redrawn depending on the film. In Circus, the border is crossed when Marion traverses from good to evil by changing her clothing from black to white. In The Cuckoo, this border is destroyed once Veikko and Ivan realize that they are not enemies after all and they reconcile. The border that establishes them as enemies is destroyed and they dress alike, reinforcing their unity. In East-West, this border is redrawn. Although Marie crosses from Western to Soviet styles of clothing, she is still treated as a foreigner. Although she crosses a physical border, she fails to assimilate, even with the proper clothing. In this case, the clothing forced upon Marie reveals a redrawn metaphorical border that she cannot cross.

As exemplified in the films, one motif can serve to define and reinforce various themes through a variety of methods. Although these themes vary from film to film, they all share a common origin. In Russian cinema, the common origin is that the motif of clothing serves to construct and define borders between opposing entities. Directors in Russian cinema select different entities to oppose each other in each film; however, each entity remains separate from its opposite through clothing. The directors of the films Circus, East-West, and The Cuckoo utilize clothing disparities to create borders between good and evil, foreign and domestic, and enemy and ally, respectively. In some films, like Circus, clothes are worn by the characters voluntarily, while in others, such as East-West and The Cuckoo, they are forced upon them. The symbolism of clothing remains the same in each film, and the limits and modes of construction of the borders produced are unique to each director.

Clothing is a dynamic symbol, and the directors apply their finesse and expertise to employ clothing in a variety of ways. The way in which they do so can create artificial borders, superficial borders, or hard borders. Furthermore, such borders can be crossed, destroyed, or redrawn. Such variety and a dynamic nature allow clothing to develop characterization and theme. Lastly, the means by which directors use clothing reveal their views on identity, which feeds into the greater concept of “otherness” that is so prevalent in Russian cinema. It is through the directors’ distinguished expertise that the malleable nature of a seemingly insignificant article such as clothing can be used so masterfully to create layers of meaning and advance a concept so central to Russian cinema.

Works Cited

Circus. Dir. Grigori Aleksandrov and Isidor Simkov. Mosfilm, 1936. Film.

East-West. Dir. Régis Wargnier. Screenplay by Roustam Ibraguimbekov et al. Dist. UGC-Fox Distribution, 1999. Film.

Fedorova, Lioudmila, and Iwona Sadowska. “Big Brother and the Other.” Georgetown University. Washington, D.C. Fall, 2012. University Course.

“Ivan wears a Soviet uniform, while Veikko wears a German one.” <http://forum.tntvillage.scambioetico.org/?showtopic=282648>. JPEG file.

“Kneishitz glares at Martinov through an icy window.” < http://www.rusfilm.pitt.edu/2006/circus.htm>. JPEG file.

“Marie and Aleksei where drab Soviet clothes.” < http://www.notrecinema.com/communaute/v1_detail_film.php3?lefilm=24683>. JPEG file.

“Marie and her family arrive in their new home in Ukraine.” < http://www.notrecinema.com/communaute/v1_detail_film.php3?lefilm=24683>. JPEG file.

“Marion, her son, and Martinov proudly march with other Soviets garbed in white.” < http://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/movie/sov/7716/foto/568/>. JPEG file.

Norris, Stephen M., and Zara M. Torlone, eds. Insiders and Outsiders in Russian Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008. Print.

The Cuckoo. Dir. Aleksandr Rogozhkin. Prod. Sergey Selyanov. Screenplay by Aleksandr Rogozhkin. STV, 2002. DVD.

“Traditional Saami Clothing.” The Cuckoo, 2002. Author’s screenshot.

“White Russian-Black Russian: Race and Ethnicity in Russian Cinema.” Russian Film Symposium 2006. The University of Pittsburgh, 2006. Web. 4 Aug. 2015.

Widdis, Emma. “Dressing the Part: Clothing Otherness in Soviet Cinema before 1953.” Insiders and Outsiders in Russian Cinema. Ed. Stephen M. Norris and Zara M. Torlone. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008. 48-67. Print.

—

Alex D. Luta is a now senior at Georgetown University on a pre-med track with a major in government and a minor in theology. He won the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s inaugural Science and Human Rights Student Poster Competition for his research on applications of geospatial technology to human rights monitoring. He has also conducted research in political science and rheumatology, for which he has been published. He wrote this essay for a freshman composition seminar on Russian and Polish film, “Big Brother and the Other,” which was taught by Professors Lioudmila Fedorova and Iwona Sadowska. The course focused on cinema as a visual language and the connection of “otherness” to identity. Alex would like to express his sincere gratitude to his professors, for their inspiration, and to his parents, for their love and support.

You must be logged in to post a comment.